We cannot ignore the tension between the need to mine for critical minerals and respecting Indigenous Peoples’ rights

- The transition to a low-carbon economy presents a profound challenge: with an estimated 50% of the world’s supply of critical minerals lying on or near Indigenous Peoples’ lands, how can we reconcile the need to mine these minerals with the equally important need to respect Indigenous Peoples’ right to have a say in how their lands are used and developed?

- There are no easy answers, and the situation is rarely black and white .

- Clarifying the distinct roles of States and companies in obtaining consent is vital, and designing decision-making processes that are meaningful and inclusive, where consent is clear and agreements are fair and equitable, should be non-negotiable.

The renewable energy transition is advancing at a remarkable pace. Across the globe, governments, corporations, and citizens are mobilising to combat climate change and build a sustainable future.

By Danielle Martin, Co-Chief Operating Officer, ICMM.

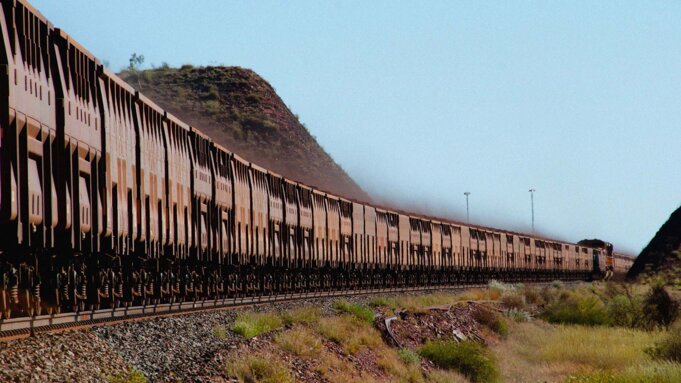

The renewable energy transition is advancing at a remarkable pace. Across the globe, governments, corporations, and citizens are mobilising to combat climate change and build a sustainable future. At the heart of this green revolution are critical minerals—lithium, cobalt, copper, rare earth elements, and others—that are essential for renewable technologies, such as electric vehicles, solar panels, and wind turbines. These minerals are vital to the infrastructure required for a low-carbon future, with demand projected to rise sixfold in the coming decades.

However, this transition comes with complex realities that we cannot ignore. It is estimated that at least 50% of the world’s supply of critical minerals are on or near Indigenous lands.[1]

Confronting historical injustices

Despite several recent examples of positive partnerships, the reality of Indigenous Peoples and resource extraction is one fraught with historical injustices. Over the centuries, Indigenous communities around the world have often been excluded from decisions about their own lands which has led, in many cases, to the exploitation of Indigenous Peoples’ territories without their consent, and without adequate compensation or remediation. In many cases, Indigenous Peoples have been left to bear the brunt of environmental degradation and social disruption caused by irresponsible mining practices.

These historical injustices cannot be overlooked, or underplayed, especially as we confront the global energy transition. Indigenous Peoples often have profound and distinct connections with their lands, territories, and other resources. These connections are tied to their physical, spiritual, cultural and economic wellbeing. Moreover, these lands are often home to some of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems, which Indigenous communities have long stewarded. Indigenous territories account for 28% of the Earth’s surface and contain 40% of its protected terrestrial areas, yet Indigenous Peoples are disproportionately affected by climate change and resource extraction.[2]

Acknowledging complex realities

The realities are complex. We must recognise that there will be difficult decisions to be made. In some cases, Indigenous Peoples may reject mining on their lands, determining that the risks to their culture, heritage, and way of life are simply too great. In other cases, they may agree to mining under terms they consider fair and equitable. And, in other instances, States may decide that – in balancing the interests of Indigenous Peoples with the broader society - certain projects should proceed without the consent or agreement from affected Indigenous Peoples, provided their rights are respected and adequate remedy is provided where rights are infringed.

The respective roles and responsibilities of States and companies around free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) processes – who is responsible for what, and when - has often been confused in a way that arguably serves no one’s interests, neither Indigenous Peoples, States nor companies. As a result, rightsholders and stakeholders have remained sceptical of the robustness of such processes.

The reality is that both States and companies have essential but distinct albeit complementary responsibilities. States are fundamentally responsible for protecting Indigenous Peoples’ rights as outlined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). This includes their duty to consult affected Indigenous Peoples in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before any development occurs on their land. At the same time, companies must respect Indigenous Peoples’ rights, exercising human rights due diligence, engaging in meaningful consultation, and ensuring that Indigenous Peoples’ consent is sought for any potential impacts on their rights (through means of an agreement).

The importance of meaningful participation, and human rights due diligence

What is essential is that Indigenous Peoples are treated as equal partners in development that affects their lands or territories. They must have the opportunity to meaningfully participate in decision-making processes, and those processes should prioritise Indigenous Peoples’ rights, enable the realisation of their development aspirations, and protect environmental sustainability.

To navigate these complexities, human rights due diligence - the process of identifying who will be affected by mining activities, understanding how they will be impacted, and taking proactive steps to mitigate any harm - must be a core part of responsible mining practices. When done properly, human rights due diligence enables good decision-making about if and how we develop natural resources for the benefit of all and without disadvantaging anyone, as far as possible. Practically, this means Indigenous Peoples can decide to freely give or withhold their consent, project developers can decide if and how to proceed and States can ensure that mineral extraction contributes to national development while protecting the environment, rights, and the interests of local communities.

ICMM has recently revised our membership commitments relating to Indigenous Peoples and mining. Member companies, which represent a third of the global mining industry, are required to obtain agreement from affected Indigenous Peoples for impacts of mining activities on their rights. This reflects our recognition that Indigenous Peoples’ rights must be respected, regardless of the legal frameworks within individual countries. It also clarifies the role of companies and States in relation to free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) and how this principle should be applied.

Building a just and sustainable future

The global energy transition is essential for addressing climate change and contributing to a sustainable future. However, this transition must not come at the expense of Indigenous Peoples’ rights, nor at any cost. By respecting the principles of FPIC, participating in meaningful engagement and conducting rigorous human rights due diligence, it is possible to reconcile the need for critical minerals with the rights and aspirations of Indigenous Peoples.

Our updated Position Statement: Indigenous Peoples and Mining can be found here.